In a recent yoga seminar I attended, a man asked the whether it would be a good idea to take his t-shirt off as a student during class, so that the teacher could see better what his body was doing and make corrections. Also as a teacher, if he took his shirt off he would be able to show students with more ease and precision how to move their own bodies. This question was raised in the context of studying BKS Iyengar’s seminal work from 1966, ‘Light on Yoga’, in which he appears shirtless in all of the photographic illustrations of the yogāsana (postures).

For me, the question itself was problematic for a number of reasons. In yoga classes, we enter a shared space. One of trust and, we hope, safety. It’s a space in which we necessarily make ourselves vulnerable in various ways in order to be curious and to explore the deepest depths and furthest parameters of the Self. In āsana, the body is the vehicle for this exploration.

When a man removes his shirt in that shared space, he is expressing the seemingly innate dominance and privilege of his body. The balance of power shifts and the space becomes male-dominated (regardless of the ratio of men to women); sex and gender become a defining characteristic of the experience.

Because women may not remove their shirts. This fact is dictated by a culture shaped through millennia of systematic objectification, sexualisation, commodification and colonisation of the female body. By a culture in which sexual violence is prevalent and normalised. Statistics show that around one in three women in a yoga class will have experienced rape and/or sexual assault. Quite possibly more, because yoga offers such a brilliant way of processing and healing from such experiences; of reclaiming the colonised body; of coming home to the Self. In this context, for a man to remove his shirt, whether as a student or a teacher, is (consciously or unconsciously) an act of power, aggression and transgression of trust. So my answer to that man’s question was, do not remove your shirt in class, recognise your privilege, and aim to cultivate sensitivity and respect (as we all must do).

So what about ‘Light on Yoga’? BKS Iyengar is shirtless in the photographs. I am glad that he is. He is showing us how to practise, through images of archetypal forms. Sometimes at home (if it’s warm enough) I practice shirtless. There’s a certain freedom in it, and a connection with the skin that can be hampered by clothes. But practising alone is a very different situation from the group learning experience.

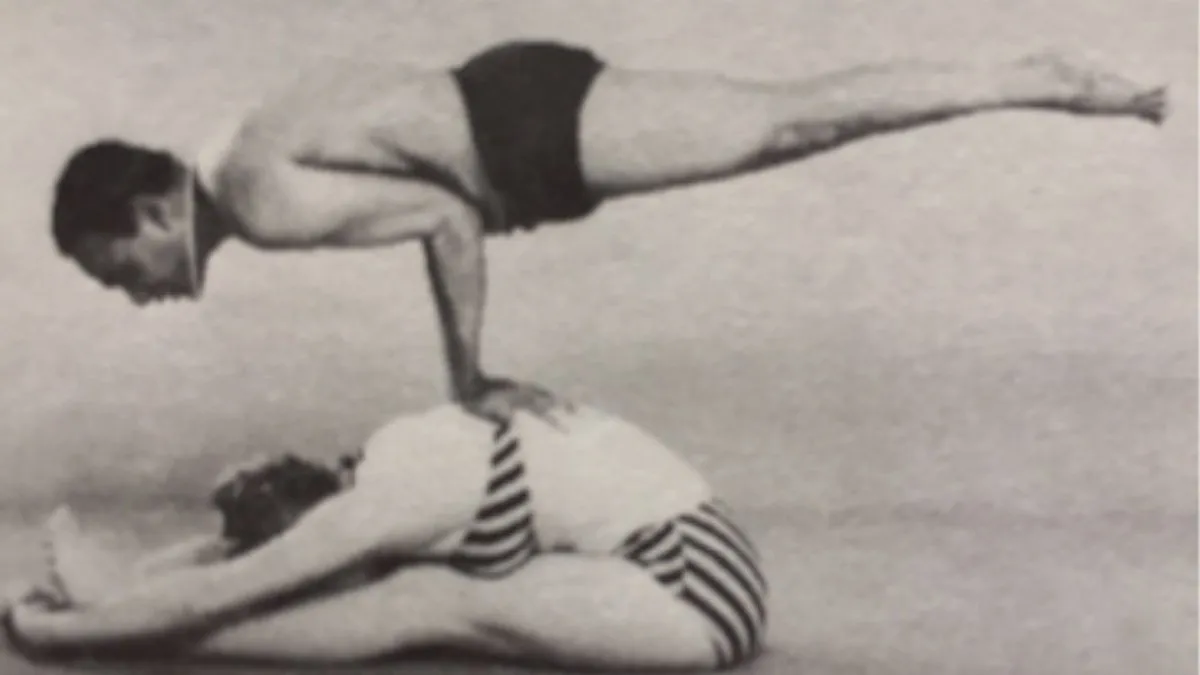

We should also contextualise this book in the era in which it was created. Iyengar’s methodology is famous for the use of props, although the book famously doesn’t depict any props at all. Not quite true. Plate 162 shows a bikini-clad woman in Pascimottanasana. BKS Iyengar is balancing on her back in Mayurasana, the whole weight of his body pressing down on her. No doubt it felt great as an adjustment, and illustrates a point about weight and balance, but nevertheless the image is disturbing; not least because, as a friend pointed out, the only ‘prop’ used in the book is a female body, in a position that is literally flattened. I don’t see that it adds much to the teaching of Pascimottanasna that the other (completely beautiful illustrations) do so well, and hope that those with the power to do so would consider removing it from future publications.

I had been nervous about initiating the conversation (sweaty, heart pumping- common symptoms of calling out prejudice) but the fact that we were then able to have a constructive conversation about it gave me courage.

In any case, back at the seminar, when I challenged t-shirt guy about his question, he was receptive and grateful. I had been nervous about initiating the conversation (sweaty, heart pumping- common symptoms of calling out prejudice) but the fact that we were then able to have a constructive conversation about it gave me courage. In a world of increasing divisions and polarisation, especially in the online sphere, opportunities to make friendly challenges in person should be grabbed with both hands, even if it feels scary. In my experience, they offer small but constructive ways to enable real changes in perspective and behaviour that will help make our shared spaces (wherever they are) open, trusting, safe and sacred.